GUEST COLUMN : Socio-economic impact of Joshimath’s sinking and the way forward

More than 65 percent of villages in Uttarkashi, Chamoli and Pithoragarh have been identified for relocation. Since 2016, these three districts accounted for more than half of the disasters in the state. It’s also shocking that even after 10 years of Kedarnath disaster the government is still not prepared enough.

One of the biodiverse areas of the planet is the Himalayas, where local populations deeply respect the natural environment. They have a storehouse of folklore, traditions and myths based on this inescapable connection that might be useful in promoting environmental preservation. Recently Joshimath town on the Rishikesh-Badrinath national highway sent alarm bells ringing across the entire region when huge cracks developed in more than 500 houses in the town. But it’s not the first time that something like this has happened in this region; there are places like Semi, Devidhar, Phata, Khat, Badasu, Dharchula, Munsyari and other places in the state which are in Earthquake Zone V and these places have in the past felt the hazardous impact of development, especially after 2013 Kedarnath floods. But this time, the size and intensity of cracks are alarming in Joshimath.

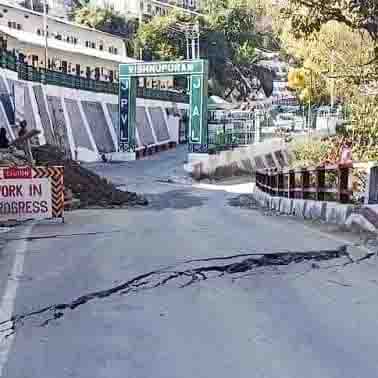

Historically, Adi Sankaracharya established a Math here around 1,200 years ago, which is the winter season residence of lord Badrinath. The Joshimath mountain is located at 6,000 feet on ancient, natural landslide material that had stabilised over hundreds of years and its terrain along with seismic zone-V make it particularly vulnerable. In 1976 an 18-member committee was set up under the chairmanship of M C Mishra, the then Garhwal commissioner, to review the causes of landslides and sinking along Tapovan to Sunil area in Joshimath. The committee recommended a complete shutdown of all the construction work in the region. The government ignored the committee’s recommendations and started big construction works on such a fragile region. Several frequent earthquakes in recent times in the Himalayas have also impacted the region. The present situation of Joshimath is the consequences of uncontrolled anthropogenic activities like the Tapovan-Vishnugad hydropower project, the construction of the Helang-Marwadi bypass, rapid urbanisation and unplanned construction.

The primary source of income in the region is tourism. Being on the highway to Badrinath, this small town has many flowing tourists. This has led to rapid urbanisation and reckless construction in the small town. It created the problem of poor drainage and sewer management in the region and is one of the causes of the recent situation in Joshimath.

It will further increase the migration in an already affected hilly region. The migration will put more pressure on already populated cities. The China border is close to Joshimath and this region acts as the first line of defence for the country. From a national security perspective, migration will make the area more vulnerable.

Joshimath and the local public existence are in danger. Many have lost their houses, and huge cracks have appeared on their agricultural land, threatening their livelihood. Also, there is a feeling of fear in people and no one is talking about their emotional and mental health. Affected families are provided shelter in rented homes in safe locations, but it’s only temporary. It has been more than a decade since the state made its rehabilitation policy. In 2011, Uttarakhand became the first Indian state to roll out a policy to identify villages at risk of natural disasters and relocate them to safer locations. Ever since the list of vulnerable villages has been rapidly increasing, the pace of rehabilitation has remained dismal. The state govt has revised the rehabilitation policy on December 31, 2021, allowed the shifting of vulnerable villages to forestland and increased the compensation amount to Rs four lakh from Rs three lakh for the construction of a house. More than 65 percent of villages in Uttarkashi, Chamoli and Pithoragarh have been identified for relocation. Since 2016, these three districts accounted for more than half of the disasters in the state. It’s also shocking that even after 10 years of Kedarnath disaster the government is still not prepared enough. It’s also a test for the political leadership; Lok Sabha Election is around the corner next year and how effectively political leadership, both at the Centre and State level, deals with such a situation and gains the trust of people will also impact the result. Political will and separate policies for the Himalayan state, especially development and urbanisation policy, are needed.

Environment-damaging development is dangerous for humanity. Every year in Uttarakhand, a large part of the state GDP is gone in disaster-affected activities. We must understand the coping capacity of the region. For such a fragile region, public involvement in decision-making with the government becomes important. The road network has grown since Uttarakhand was formed, going from 8,000 kilometres in the year 2000 to 50,000 kilometres in the year 2022. The debris from the road ends up in the river creating a monsoon-like flood condition.

The three E’s- Environment, Ecology and Economy- are necessary for sustainable development in such a sensitive region. No effort is being made to undertake economic growth projects sustainably and equitably. The government is bent on rapid economic growth in which neither nature nor people matter. Is making people aware and sensitising them through education sufficient? Even in the 21st century, if we cannot understand nature’s value, then nature will impose its solutions. The ensuing disasters will force people to become more sensitive towards preserving nature. The time has come when we need to follow our traditional knowledge. The long-term future of humanity depends on keeping the gap between scientific progress and traditional ecological wisdom to a minimum. Long-term futuristic policy is needed for this sensitive Himalayan zone. But the development should be sustainable within the context of the region’s ecology, geography and cultural features.

(Semwal is head of political science department in HNB Garhwal central university, Rawat is a senior research fellow in the same department. Views expressed are personal)