After Gandhi’s assassination, embattled RSS decided to ‘grow political teeth and wings’

VIEWPOINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

In course of conversation years ago at the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) headquarters in Calcutta- a little away from the ancestral home of Swami Vivekananda- a veteran RSS pracharakwho was also a senior state BJP leader told me that the then Sangh chief MS Golwalkar (better known as Guruji in the saffron circles) had earnestly pleaded with the Bharatiya Jana Sangh founder Shyama Prasad Mookerjee not to embark on his scheduled Kashmir march, defying the permit system that was then an imperative for those entering Jammu and Kashmir from outside the state. Golwalkar told Mookerjee- as the RSS pracharak recounted to me–that he was overcome with a sense of ominous foreboding that something bad might happen to him. But Mookerjee had already steeled his mind to enter J & K, sans permit, regardless of consequences.

The rest is history. Prof Bal Raj Madhok wrote in his book, ‘Portrait of a Martyr’, “Thousands of voices were heard chanting Jai Bharat Mata Ki and Bharat Kesri Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerjee as the passenger train carrying Dr Mookerjee to Punjab on his way to Jammu steamed out of Delhi railway station at 6.30 a.m. on May 8 1953. The compartment in which he sat had been decorated with flowers and Jana Sangh flags. Vaidya Guru Datt, Atal Behari Vajpayee, Tek Chand and the author accompanied him in the same compartment. A few pressmen also joined us.”

However, the focus of this article is not on the fatal Kashmir march of the Jana Sangh founder but on why and when the RSS which had vowed to eschew politics decided to align itself with a political party.

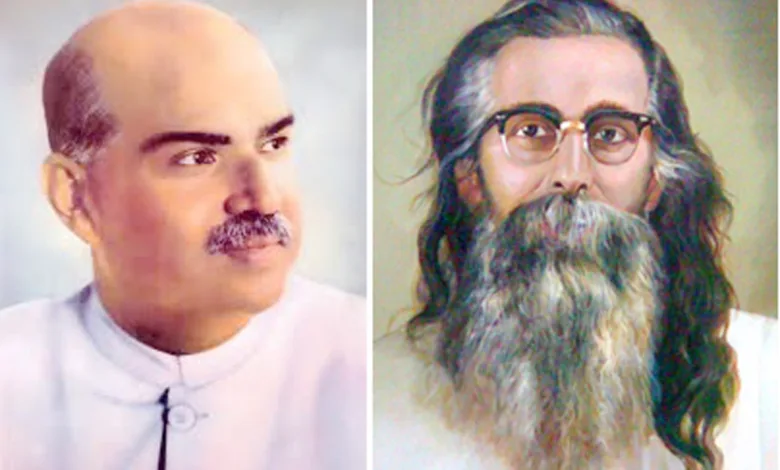

The RSS was founded by a disillusioned Congress leader Keshav Baliram Hedgewar in Nagpur in 1925 at a critical crossroad of the history of undivided India when the Congress leaders, who were followers of the ideology of nationalism propounded by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Aurobindo Ghosh, were bitterly resentful of the Gandhi-led Congress’s ‘supine surrender’ to the Islamic fundamentalists in its ‘chimerical’ bid to bring the Muslims into the anti-colonial movement. Once a staunch Congressman, Hedgewar was sent to jail twice-during the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921 and again during the Civil Disobedience Movement in 1930-31.

Interestingly, Mahatma Gandhi was present at the RSS congregations twice on Hedgewar’s invitation. The former BJP vice- president KR Malkani wrote in an article, “The RSS, along with millions of people, did not approve of Gandhiji’s Muslim appeasement policy…but it had the greatest respect for the Mahatma. Indeed Gandhiji had visited the RSS winter camp in Wardha in December 1934 and addressed the Delhi RSS workers in a colony of low caste residents in September 1947. He had deeply appreciated the ‘noble sentiments’ and ‘astonishing discipline’ of the RSS.” However later, Gandhi’s view of the RSS underwent a sea change. But I will not get into that here.

Still more interesting, Jawaharlal Nehru who was a fierce critic of the Sangh ideology praised the RSS twice-first when the saffron volunteers had gone to help after Pakistan-backed Pathan warriors invaded then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir soon after independence and again when the RSS cadres had helped the Indian Army during the 1962 Chinese aggression. A pleased Nehru invited the RSS to take part in the 1963 Republic Day parade.

But things changed perilously for the RSS after Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and the vitriolic nationwide condemnation of the assassin Nathuram Godse and his links with the RSS. Let me quote Malkani again. “But after his (Gandhiji’s) killing, 17,000 RSS workers, including Shri Guruji, were accused of conspiracy of the murder of Mahatma Gandhi…But during all this time, not one MLA or MP raised the issue in any legislature. For the RSS, it was the moment of truth….unless the RSS grew political teeth and wings, it would always be at the mercy of unscrupulous politicians. This was the context in which Shri Guruji blessed the birth of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh under the leadership of Dr Shyama Prasad Mookerjee.”

However, things were far from smooth. Bal Raj Madhok wrote in his book that the RSS leadership was not clear in its mind as to the shape and character of the political party to which it might lend support or the role it would have to play if it decided to bring a new party into existence. The RSS veterans were doggedly opposed to the idea of the RSS identifying itself with any political party. They feared that it would inevitably pull the organisation down from the high pedestal of a common platform for those who were votaries of the core ideology of the RSS across the political spectrum to a narrow and exclusive political group. “Politics, they feared, would corrode idealism and spirit of selfless service to the society in the RSS… As against this old guard was a younger group of senior workers who were all out for securing political support for the RSS through a political party,” Madhok wrote.

With ideological/pragmatic churning continuing in the RSS’s higher echelons for a long time, the dithering finally ended as a compromise formula evolved under which the RSS would retain its identity as a social and cultural organisation as before and yet it would actively support a political party to which it would spare some senior workers aside from allowing it to use the organisation’s goodwill.

Meanwhile, after quitting the Nehru government anguished over its ‘bungling in Kashmir’ and the massacre of the Hindus in early 1950 in erstwhile East Pakistan, Mookerjee was impatient on forming a political party of his own, Madhok wrote. He further wrote that Mookerjee had made it clear to the RSS leadership that if the latter failed to support him he was prepared to go alone. But the RSS kept dithering again. A daunting challenge loomed for it: whether to approach Mookerjee or not, given his towering national stature as an independent-minded leader. They knew that Mookerjee was most unlikely to play second fiddle to anyone else. Finally, the ice thawed as Golwalkar and Mookerjee met.

Mookerjee’s view of Hindutvawas quite loud and clear. To dispel the misgivings prevailing in the minds of some of the leaders of the nascent Jana Sangh, he gave a clear exposition of what he thought about Hindu and Hindutva. He said it was due to the British’s imperialistic machinations that the term Hindu was given a narrow, sectarian connotation and the Congress, influenced by the Western thinking, was inclined to denounce everything Hindu as communal. But for him, Hindu was a noble concept that underlined the basic oneness and common traditions of all the different sects and creeds of India. In no way did it mean a particular religion but a vibrant commonwealth of all religions and sects of the country and irrespective of the way of worship of individuals, no section of Indians should break itself away from the cultural mainstream of the country.