Catch-all Congress riddled with inherent ‘communal’ fault lines

Sunday, 04 February 2024 | Romit Bagchi

VIEW POINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

Indian National Congress emerged as a supra-communal organisation, as a community of temporal interests and not of spiritual convictions, visualised as a vibrant common platform where Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis and others, representing respective communities, would discuss their secular affairs.

However, soon after its inception, the communal fissure surfaced. A resolute attempt to pass a resolution calling for ban on cow slaughter was made during its Madras session in 1887 and it was thwarted with the majority of the delegates passing another resolution that stated there should be no discussion on any subject to which either Hindu or Muslim delegates were unanimously or near unanimously opposed. Relieved over the ‘communal’ resolution being crushed, the veteran Congress leader Surendranath Banerjea observed that now their Muslim friends should not hesitate to join their Hindu brethren.

It was an uncertain time with the seeds of Hindu resurgence movement having already been sown. Five years before Banerjea made this conciliatory statement, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Anandamath which contained Vande Mataram- which was to become the rallying cry of the freedom struggle- had been published. It was again the time when a young Narendranath Datta was preparing to awaken India- wallowing then in deep slumber oblivious of its glorious past- under the influence of his spiritual mentor Ramkrishna Paramhans.

So, the respite the secularists got was short-lived. The amorphous Hindu nationalism got concretised with the emergence of the vigorous movement based on the twin principles of Swaraj and Swadeshi in the aftermath of the Colonial government’s decision to partition Bengal. Led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Bipin Chandra Pal and Aurobindo Ghosh, the new force representing uncompromising rejection of the foreign rule based on the bedrock of a robust Hindu resurgence made a full blast appearance and subsequently, the Congress was divided into two major factions-Moderates and Radicals-marking a significant ideological division that ended up in its first split during its tempestuous Surat session held in 1907.

Let us see what happened at Surat. The Moderate leaders were set to foist a new constitution on the Congress meant to block the Radical bloc from commanding majority at the party’s annual sessions. The younger nationalists were determined to thwart the plan, ready to break the Congress if they could not propel it into their ideological mould. Tilak stood up to speak on the resolution he was about to table, but he was not allowed. Tilak being adamant to speak, an uproar ensued. Amidst the melee, some Gujarati volunteers lifted up chairs over Tilak’s head to beat him. In a retaliatory gesture, a Maratha youth hurled a shoe that came hurtling across the pavilion aimed at the president of the session Rash Behari Ghose and hit Surendranath Banerjea on the shoulder. TheMaratha youngsters then charged up to the platform, making the Moderate leaders flee. A fight ensued on the podium with chairs thrown hither and thither and the session broke up abruptly.

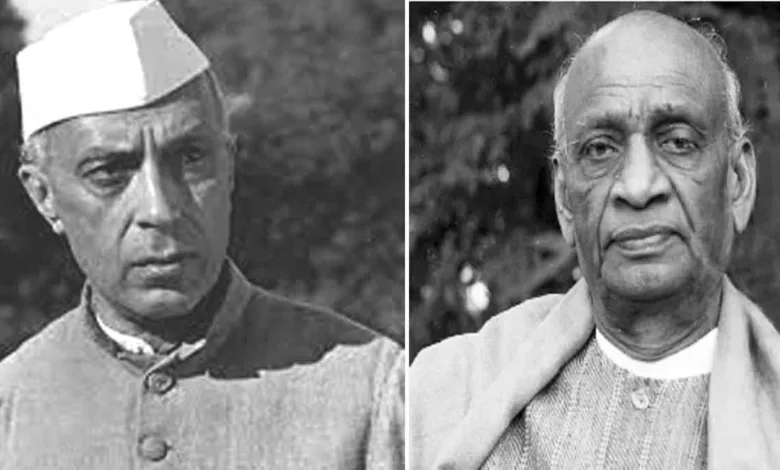

The long-smouldering conflict between the two apparently incompatible ideologies became overtly bellicose a few months after the enforcement of the Constitution and a few months before the country’s first general election. Another major split was then staring the Congress in the face on the issue of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘weak-kneed’ policies towards Pakistan and the Muslim minority left in India. Two formidable factions-one led by suave Nehru and the other by doughty Vallabhbhai Patel- locked horns as the party was preparing to elect its new president. Amid the loud squabbling with both sides refusing to budge an inch from their respective stands, Sampurnanand- a hardcore Patel loyalist from Uttar Pradesh- proposed the name of Purishottam Das Tandon as the next Congress president, to the chagrin of Nehru.

There are reasons behind Nehru’s exasperation. The relation between Nehru and Tandon-both from Allahabad- had been bitter. Let us look back at history to understand the backdrop. The Congress Working Committee passed a resolution accepting the partition of India on June 12, 1947 and the same was to be ratified on 14 June by the All India Congress Committee. It was then that the long-stifled emotions exploded. Tandon was one of the most vociferous dissenting voices inside the Congress. He beseeched the AICC members to reject the partition resolution lock, stock and barrel as it was, in his view, tantamount to supine surrender to the scheming British government and the bullying Muslim League. He said without mincing words that the proposed vivisection on religious lines-mooted in weakness and despair- boded ill for both the Hindus in Pakistan and the Muslims in India as they would be compelled to live in perpetual fear.

Some insiders revealed that the relation between Nehru and Tandon was so bitter that affable Lal Bahadur Shastri had to often intervene to water down the tension abounding between them.

The move to thrust Tandon on him as the party president naturally angered Nehru and he wrote to Tandon, who had been conferred with the title ‘Rajarshi’ by Mahatma Gandhi and who had rejected ministerial berth post-Independence, to withdraw from the contest. “…I have often read your speeches with surprise and distress and have felt you were encouraging the very forces in India, which, I think, are harmful… I think the major issue in this country today, if it is to progress and to remain united, is to satisfactorily solve our own minority problems. Instead of that, we become more intolerant towards our minorities and give as our excuse that Pakistan behaves badly…Unfortunately, you have become, to large numbers of people in India, some kind of a symbol of this communal and revivalist outlook.”

But Tandon refused to wilt, backed by Sardar Patel and Govind Ballabh Pant. His annoyance having changed to anger, Nehru threatened to quit the government and the Congress Working Committee if Tandon got elected. Still unable to coerce him into submission, he persuaded J B Kripalani, a staunch critic of Sardar Patel, to contest the election. However, foiling all rhetoric and actions, Tandon defeated Kripalani convincingly to become the president. Refusing to accept his election, Nehru now switched his anger on Sardar Patel who was then heading the crucial department of State. With intensification of bellicosity, Nehru drafted a letter to inform Sardar Patel that he was being divested of this ministry. Nehru’s biographer S Gopal writes, “The letter was not sent, probably because Nehru knew that Patel was now a dying man…”

In August 1951, Nehru quit the CWC followed by en masse resignation of all the CWC members, leaving Tandon in an untenable position with his mentor Patel having meanwhile died. Tandon stepped down in September 1951 leading to Nehru taking over as the Congress president. And then the Congress ceased to be the coalition of ideologies that it always was unlike the ideologically regimented parties and got reduced to a fossilised party, frozen in the bigoted groove of Nehruvian secularism.