GUEST COLUMN : Rehabilitation or forced displacement: a case study of sinking Joshimath

The year 2023 marks 50 years of the famous Chipko movement which was a cultural expression of the people’s love for their environment. Uttarakhand, the land of gods, is renowned for its breathtaking landscapes, diverse wildlife and rich culture. Nevertheless, shocking events like the Kedarnath flood, Rishiganga floods and now Joshimath subsidence tell a different story. What have we done to this Devbhoomi Uttarakhand in the name of development? Has all the sacrifice of the brave freedom fighters of this land gone in vain? The main reason for the development in the mountainous region is to stop migration, but this uncontrolled and excessive development has led to more migration from the mountains. If people do not live in the mountains, then for whom we will facilitate this development? There is a famous saying about the mountains and its people which states that the roads in the mountains are zigzag, but people are straightforward. It has been more than two decades since Uttarakhand was formed but natural disaster has immensely affected this State. These calamities have also been provoked by anthropogenic activity in the name of development. It is not that the people of Uttarakhand did not make efforts to protect this environment. Uttarakhand is also the land of renowned environmentalists like Gaura Devi, Sunderlal Bahuguna, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Kalyan Singh Rawat and others. Chipko is a traditional practice of people’s affection for their environment.

Pahadi poet Mahesh Punetha has rightly described the development situation in the mountains with his poetic lines “Sadak tum ab aayi ho gaon, jab sara gaon shahar ja chuka hai” These lines perfectly depict how beneficial the development in the mountains has been. The sinking of Joshimath is not the first such case and will not be the last in the Himalayan region. The first step is to ensure the safety of the people and it is easy to talk of evacuating the place. However, people need to talk about mental health of the people. In addition to the social and economic losses, people also suffer from mental instability, anxiety disorders and depression. The rushed evacuation has left many residents emotional. The emotional miseries a person experiences after a disaster are incomparable to the social and economic losses that disasters often cause.

The role of the NTPC project is definitely in question. Land use restrictions are there for the people in the State, but what about the governmental constructions? Has the Environmental Impact Assessment been considered for constructing these significant projects in the Himalayan region? The Ravi Chopra committee set up by the Supreme Court to study the impact of receding glaciers on hydroelectric power projects (HEPs) after the 2013 Kedarnath disaster recommended a ban on the construction of hydro power project dams in the paraglacial region. This NTPC project of Joshimath is in the same MCT paraglacial region. Hydropower generated little State revenue despite its economic potential. Uttarakhand’s 2021-22 budget estimates hydropower revenue at Rs five billion, less than one per cent of the State’s entire budget.

The increasing use of concrete and cement structures in place of traditional wood and stone masonry is accelerating the mountain region’sregion’s heat-island effect. As a result of global warming, an increasing number of glaciers are disappearing completely or retreating, and there is significantly less snow. Heavy vehicles and vehicular pollution resulting from the Char Dham Yatra have also affected the Joshimath environment. They have led to the collapse of land in significant areas of the Char Dham route.

Since they have lost their conventional homes and cannot afford to construct new ones, many now reside in relief camps. The breakdown of the family, kinship networks and other community support systems puts people in severe difficulties. Many people of the region depend on tourism as a source of their livelihood and a large section of people in the Joshimath village area survives by selling milk. It is not the resettlement but forced displacement that hurts the people of Joshimath more. People are afraid that they will lose their identity and culture connected with the town and will never be able to return to their hometown. After a tragedy or other traumatic experience, emotional instability, stress reactivity, anxiety, trauma and other psychiatric symptoms are common. These psychological impacts have a significant influence on both the affected individual and the community. Resilience is an essential factor to consider and an effective measure.

The education of the students has been impacted majorly because of the chaos in the town. Board exams are around the corner and students are worried about their future. Most of the schools currently are closed in the town because of winter vacation. Joshimath is a centre for the board examination and every year hundreds of students from nearby villages come here for their board exam. Since cracks have developed in school buildings, there is still uncertainty about the exam among the students. These children are going through a lot, making it challenging to prepare for the exam as most are busy shifting their things.

In the case of Joshimath, the critical concern is how long it will take for them to get their new home or whether they will ever get a new home. Money is only a temporary relief. Though the revised rehabilitation policy allows the shifting of vulnerable villages to forest land, the challenge of land availability in the State is still there. If the government relocates these people to the plains, it takes many years to adjust to a new place. They will face many issues like health issues due to environmental changes. One thing is obvious- forced displacement affects both men and women, but its impact is felt more by women, the aged people and children. The government’s rehabilitation policy is quite complicated and there are several gaps in the policy. We have seen in Tehri resettlement that problems are still so complicated that they caused disputes among individuals and the majority of cases end up in court.

Of the 484 villages in Uttarakhand at risk from natural calamities, more than 450 are waiting to be relocated. People have now undoubtedly realised that they live in a susceptible zone of the Himalaya with the recurrence of disasters likely at an undesirable frequency.

The Joshimath incident is an eye-opener for the people to have insurance over their assets. In a mountainous region, people generally do not insure their assets. The misconception about the costly nature of insurance also needs to be cleared. Insurance will also reduce the burden on the public exchequer.

Joshimath is a gateway to the shrine of Lord Badrinath and managing the upcoming Char Dham Yatra will be a major challenge for the government. Now policies need to be built around disaster management in the State. After all these years, the State’s Disaster Management department is temporary. Most of the employees of the department are contractual/private. Even political parties need to include this in their manifesto in the future. Sustainable development demands approaches that are both geologically and ecologically sound and it is such approaches which are needed. Considering that climate risks to slope stability are becoming far more unpredictable, such development also improves disaster resilience and enhances national security. During the Char Dham Yatra season, the government should also explore adopting CNG or electric vehicles. The time has come when we must understand the value of the majestic Himalaya. Disaster and development are dynamic and their excellent or harmful effects rely on the local community’s particular social and cultural characteristics along with disaster and development management capabilities. What this Himalayan State needs is more than just creating policies. The problem is the separation of the laboratory from the land. Any decision taken in haste at this time can cause problems in the future. Plans for rehabilitation should be developed with the community’s cultural context and the affected population’s needs in mind. Then the community will be holistically prepared to deal with future crisis. Development should be done keeping in mind environmental ethics otherwise we will have to pay the price of development. It is time for the government to develop a Himalayan model of development by considering the opinion of the region’s local people in decision-making. In a democratic country, the concept of the welfare State will be fulfilled only when the laws or actions of the government are for the benefit of the citizens of the country.

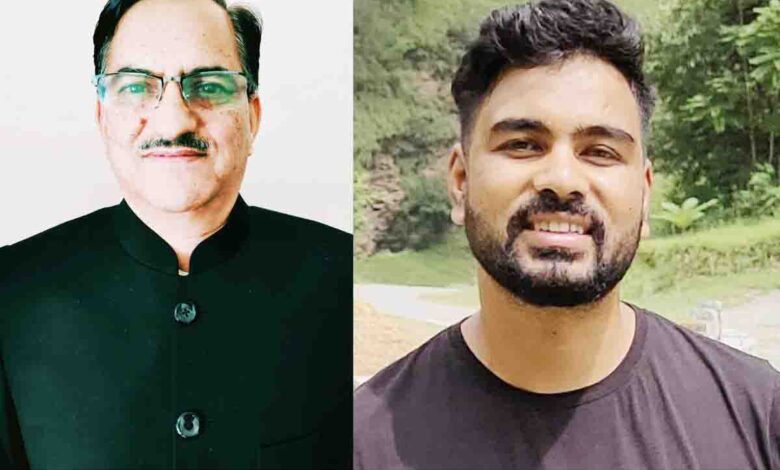

(Semwal is head of political science department in HNB Garhwal central university, Rawat is a senior research fellow in the same department. Views expressed are personal)