‘One-man boundary force’ kept Bengal riot-free in fateful August, 1947

VIEW POINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

As the clock struck midnight on August 15, 1947, India broke free from the shackles of British domination and became a free nation. In a simultaneous event of stupendous importance, Pakistan, cleaved from the British-ruled India, was born. The two successor States- born amid appalling migrations unprecedented in human history- descended into carnage and conversion with the Hindus and Sikhs wending their way into Hindu majority India and the Muslims streaming into the new Islamic State carved out of the body of India to provide them a homeland.

But what was happening in Delhi on that momentous midnight? After Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had delivered his unforgettable ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech in the Constituent Assembly, he along with the president of the Constituent Assembly Rajendra Prasad went to the residence of then Viceroy Lord Mountbatten to request the latter to assume the post of the first Governor General of free India. Overwhelmed with ecstatic excitement, Prasad kept fumbling in his speech and Nehru had to prompt him in every sentence to help him complete it. And what Nehru did? He went with an envelope that was supposed to contain the list of the members of his council of ministers to be handed over to Lord Mountbatten. After they had left, Mountbatten opened the envelope to find it was empty. Being on cloud nine, Nehru had forgotten to put the list in it.

When Delhi was merrily rejoicing the advent of freedom with flag hoisting and fireworks, things were terrifying on the western border of partitioned India. The long-smouldering communal embers turned into a veritable inferno on August 14-the day Pakistan came into being. It saw the massacre of Sikhs who gathered at Lahore railway station to migrate to India. Retaliation followed as many Muslim women were raped and murdered at a bazaar in Amritsar on August 15. With the spiral of violence intensifying every hour, the Sikh families who had taken shelter in a Gurdwara in Lahore were burnt alive. The flames ripped through Sialkot and Sheikhpura in West Punjab under Pakistan where a number of Sikhs were massacred and maimed. The Sikhs hit back with equal savageness in Amritsar. The fire- fanned by wild rumours coming thick and fast- engulfed Patiala, Meerut, Saharanpur, Alwar, Bharatpur and finally Delhi.

But during this perilously volatile time amid the sanguinary pangs of Partition, what was happening in Bengal? Though battered severely by the frenzy of gore unleashed during the ‘Great Calcutta Killing’ followed by equally terrifying Noakhali riots exactly a year ago, it was incredibly calm, free from riots. Not only was that but the Hindus and Muslims, gathered in spectacular camaraderie, ushered in the new era of Independence together.

Nehru in his midnight speech emotionally referred to Mahatma Gandhi: “On this day our first thoughts go to the architect of this freedom, the Father of our Nation, who, embodying the old spirit of India, held aloft the torch of freedom and lighted up the darkness that surrounded us.”

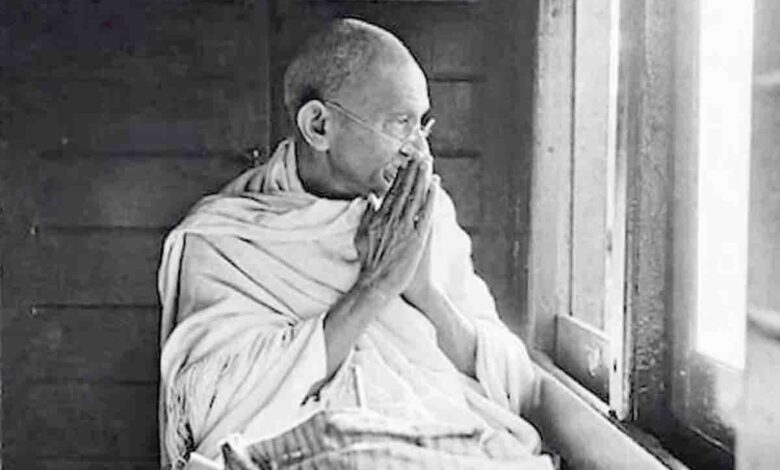

But where was Gandhi that night? Far away from the triumphant exhilaration of illuminated Delhi, he sat in a semi-dark room at an abandoned mansion in east Calcutta on fast, staring mournfully at the sepulcher of his life’s cherished dreams. Requested by a senior officer to give a message on freedom, he declined, saying he had no message to give. “I have dried up, completely,” he muttered. And it was this frail old man whose saintly presence kept Bengal riot-free during that combustible time.

A renowned poet Amiya Kumar Chakraborty gave a moving account of those days in Calcutta to an American scholar Gene Sharp. When men would come back home after their day’s work they would find their wives waiting to serve them their dinner, but later they would find that their wives were fasting. Asked, they would say that when the Mahatma was embracing death by fasting to atone for their sins of fratricidal violence how they could take food.

Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India and the first Governor-General of Independent India, wrote a letter to Gandhi on August 26: “… in the Punjab, we have 55 thousand soldiers and large-scale rioting on our hands. In Bengal, our forces consist of one man and there is no rioting… As a serving officer as well as an administrator, may I be allowed to pay my tribute to the One-Man Boundary Force?”

What was Gandhi thinking that night? We may presume he was wondering forlornly over his closest lieutenants having morphed overnight from uncompromising idealists into calculating realists prioritising power over principles. Darkness felt within and without, he was as though witnessing glumly the funeral of the Congress which he had transformed from an organisation confined to the landed aristocracy and intelligentsia into a mass movement platform to challenge the seemingly invincible might of imperialism. To stem the tide, he had suggested dissolution of the Congress on attainment of Independence with its leaders becoming volunteers and spreading out the length and breadth of rural India to act as vibrant localised centres of rural empowerment. “…without the backing of constructive work and penetrating the villages, their legislators would practically be idle and the voters would be exposed to the machinations of vote-catchers,” he had warned. But there were no takers for his ‘utopian’ postulate for Congress revival.

Inimical to a negotiated freedom through fragmenting the country into two mutually bellicose parts, Gandhi was for leading the people to snatch away freedom through another full-blooded movement burying the communal cleavages. But the Congress leadership was singularly cool. Pandit Nehru himself told his biographer Michael Brecher that they had aged and were too exhausted to embark on another all-out movement. In a prayer meeting on July 20, 1947, Gandhi murmured: “I have been a rebel all my life. How can a rebel cry?”

The Congress Working Committee passed a resolution agreeing to Partition on June 12, 1947. When it was to be ratified by the All India Congress Committee two days later it faced stiff resistance from a sizable section of its members. Sensing the belligerent mood, the party brass did not invite Gandhi in the day’s session. But as things got stuck in a stalemate with the dissenters resolutely sticking to their ‘no to Partition’ guns, Gandhi was brought in the afternoon session. The helpless ‘supremo’ feebly supported the ruling clique of the party, saying that though unshakably convinced that Partition would spell disaster for the two successor States, he was urging the members to endorse the Partition resolution not only to help the party stay united during that dangerously volatile time but also to avoid a debilitating uncertainty plaguing the nation.

While many reluctantly fell in line following Gandhi’s faint-hearted exhortation, a section of the AICC members led by Purushottam Das Tandon voted against the resolution.