Partition climbdown: The mystery of evolving Gandhi

VIEWPOINT

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

This year’s Durga Puja reminded me of a controversial puja held in Kolkata last year. That was the puja organised by the All India Hindu Mahasabha. It stoked a fierce row, warranting the intervention of the Home ministry. It was because Mahishasura’s idol bore resemblance to Mahatma Gandhi. The organisers declared proudly that they considered Mahatma Gandhi the real asura responsible for the gory partition of Bharat. Later, they had to remove the idol of Mahishasura under pressure put on them from the Home ministry brass.

The Hindu Mahasabha since its very inception has been critical of what it dubs the blatant Muslim appeasement of Gandhi that finally culminated in the horrors and anguish of the ancient land’s partition on communal lines.

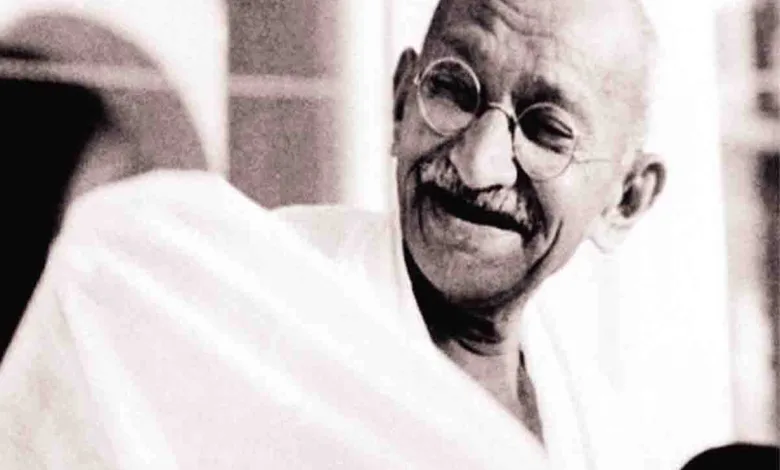

Mahatma Gandhi was an enigma for his contemporaries and he is even more so now. One can hardly sum up a life that is larger than life. He had a personality that transcended the confines of rational, logical thinking. He has been studied by academics of all disciplines, including those pursuing psychoanalysis, for years on end and yet the mystique of the Mahatma continues. His persona remains elusive, shrouded in inscrutable mysteries, layer upon layer, and it seems impossible to deconstruct the ‘saintly idiosyncrasies’ he personified. The more we study the more we find that we have failed to correctly understand the real Gandhi and we feel we should go for further research. Even 75 years after his death, he is being remembered across the world for right or wrong reasons.

During the momentous phase of the country’s anti-colonial struggle, both the Communists and the Hindu Sabhaites kept on criticising him, from different perspectives though. While the Communists criticised him for his antipathy to the concept of class struggle and his stress on class cooperation the Sabhaites lost no opportunity to project him as the greatest enemy of the Hindus for his invincible propensity of “supinely kowtowing to the vicious, divisive machinations of the Muslim League.” Yet, they had to admit albeit grudgingly his hypnotic hold over the Indian people. They knew quite well that whatever he would decide and advocate would be accepted by a large body of the people.

The former USA President Henry Ford famously proclaimed in 1916 that history was more or less bunk. Later, he explained his comment, saying that he had meant written history focused on political leaders and military heroes being bunk. But for many, history is fascinating and it holds lessons in it. This is particularly so if it is an account of a nation’s journey through the vicissitudes of a volatile time helmed not by political leaders but by the builders of the nation. Mahatma Gandhi was not an ordinary political leader; he personified determination and dilemma, strength and weakness, hope and despair of a fledgling nation. So, the history of how his view of the demand for Pakistan evolved over time from unshakable opposition to poignant acceptance never ceases to be fascinating.

Let us now look back on history. In 1937, the Muslim League during its Lucknow session found that the Muslim populace across the subcontinent was being swayed for the first time by its anti-Congress stance and its demand for partition. Time also favoured its ascendancy. As the Congress’s resolve to fight for the country’s independence grew stronger after the outbreak of the Second World War, the British government started hobnobbing with the League with more malicious vigour than before. The then British Viceroy Lord Linlithgow rejected Gandhi’s claim to be the sole representative body of all Indians and averred he would consult “representatives of several communities, parties and interests in India” over the future of India, thus shrewdly setting the stage for partition.

With the League upping the ante on its demand of Pakistan, what Gandhi wrote in the March 1940 issue ofhis mouthpiece Harijan is quite baffling: “If the vast majority of the Indian Muslims feel that they are not one nation with their Hindu and other brethren, who will be able to resist them?” In the next issue of Harijan, his view seemed to have softened further on the demand of Pakistan. He observed: “The Muslims must have the same right of self-determination as the rest of India has. We are at present a joint family. Any member may claim a division.” Yet, in the same article he wrote: “The two nation theory is an untruth. The vast majority of Muslims of India are converts to Islam or are the descendants of converts. They did not become a separate nation as they became converts.” What he wrote in the next issue of Harijan is even more interesting. “As a man of non-violence, I cannot forcibly resist the proposed partition if the Muslims of India really insist upon it. But I can never be a willing party to the vivisection. I would employ every non-violent means to prevent it.” During this tumultuous time, an anguished Gandhi told the Muslim League leaders that they were “trying to do something which was not attempted even during the Muslim rule of two hundred years.” The enigmatic aspects of Gandhi’s persona deepened further when he wrote around the same time: “…if the eight crores of Muslims desire Pakistan no power on earth can prevent it, notwithstanding opposition, violent or non-violent.”

When it became clear that Gandhi had finally acquiesced to the principle of partition, then Hindu Mahasabha president Syama Prasad Mookerjee declared in a tone of anger and anguish: “If Gandhiji barters away the rights of the Hindus and the country by accepting the principle of partition, the Congress may not oppose him but the Hindu Mahasabha will deem it a sacred duty to rouse the people against an impending disaster that may ruin the country for good.”

Let us recall that the same Gandhi had earlier asserted that if the Congress wished to accept partition it would be over his dead body. “So long as I am alive I will never agree to the partition of India,” he had assured the people of India. So, why did he come off the high horse? What happened in his subjective world that led to such a volte face on an issue as momentous as partition of the country? Was it wisdom of accepting the inevitable or was it an outcome of pressure put upon him of reconciling to the fact of partition or was he reduced to a helpless puppet, shorn of energy to act, a life-weary, old man waiting impatiently to embrace death contrasted with his earlier desire to live for 125 years?

We will never get answers to these questions and so the mystique of the Mahatma will continue to haunt us for many, many years to come.