Radhika will no longer dance in Madhuban

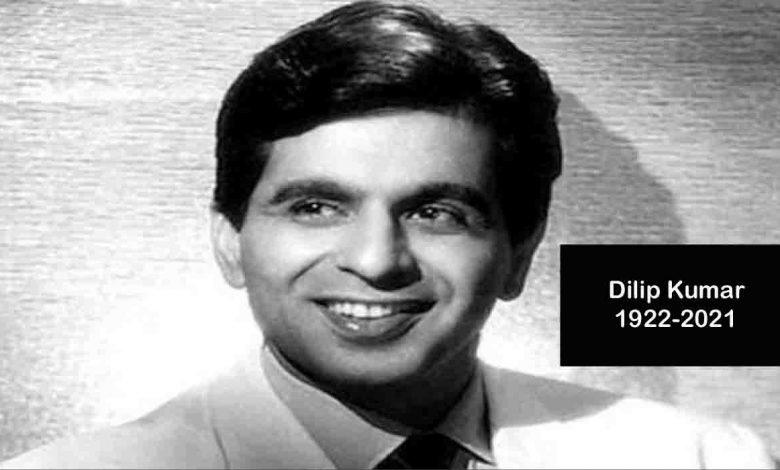

Thursday, 08 July 2021 | Saimi Sattar | New Delhi

Music composer Naushad often remembered how during the shooting for Madhuban Mein Radhika Naache Re, for the film Kohinoor (1960), actor Dilip Kumar learnt how to play the sitar. To get the hand movements during the shooting right, tabla maestro Zakir Hussain has been quoted saying that the actor trained for six months with the renowned sitarist Ustad Halim Jaffar Khan sahib before the filming of this song. This, at a time, when method acting was an unknown entity for the Hindi film industry gives a small peek into the perfectionism of the Pathan from Peshawar, who — for a major part of his life — called Bombay (later Mumbai) his home.

But this was not the sole instance. Stories abounded about his quest for delving deep into the skin of the character, which paid dividends to his on-screen persona but led to disastrous consequences for the man himself.

Kumar drank himself to desperation and near depression to bring Devdas (1954) alive on screen. This was just one in the series of back-to-back tragic portrayals that earned him the title of “tragedy king” which also threatened to be his undoing. So immersed was he in the characters that he was advised by his psychiatrist to play light-hearted roles. This made him refuse the iconic Pyaasa and the jury is still out if the film would have become as much of a landmark, as it did, if Kumar played the role of Vijay — the unsuccessful poet — essayed by Guru Dutt.

Respecting K Asif’s understanding of the grandeur and respect due to the future emperor of India, he did not lip-sync to a single song in Mughal-E-Azam (1960).

For Gunga Jamuna (1961), Kumar ditched his refined upper-class Urdu to speak Bhojpuri like his gardener in Deolali (where he spent a considerable time while growing up for the sake of his ailing brother and mother) as if he was born conversing in it.

Dilip saab, as the industry fondly called him, was not just an actor, he was an institution, a school at the feet of which generations of actors drew sustenance and inspiration for their craft. Dotting every decade, these include the likes of Rajendra Kumar, Manoj Kumar, Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Naseeruddin Shah, and more recently, Shah Rukh Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui.

While reams are written about Kumar’s play at tragedy, his flair for comedy in films like Ram Aur Shyam (1967), Leader (1964) and his body’s innate sense of rhythm when he danced (Nain Ladh Jainhen and Uden Jab Jab Zulfen being the two examples that immediately come to mind) are proof that when he put his mind to something, the results were unsurpassed.

He was born Yusuf Khan, on December 11, 1922, on a night which was characterised by a raging fire in the Goldsmith’s Lane in Qissa Khwani Bazar where his ancestral house was located. A bone-chilling blizzard added to make the night more tumultuous. While the actor himself made light of the events, his paternal grandmother believed that his arrival in the midst of the blizzard and the fire meant something significant. When a wandering faqir proclaimed later that “This child is made for great fame and unparalleled achievements,” she felt validated. This account, quoted in Dilip Kumar: The Substance And The Shadow, An Autobiography, did come true and how.

When his father, a fruit wholesaler, moved to Mumbai, his mother and siblings soon followed suit. Young Yusuf had no plans of being a part of the film industry, though at Khalsa College — where he studied — he counted Raj Kapoor, the son of the renowned actor Prithviraj Kapoor as one of his closest friends. Later, it was with Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand that he went on to become the troika that dominated the Hindi film industry from the 1940s to 1960s.

What made Kumar different from Kapoor’s Charlie Chaplin’s tramp act and Anand’s suave characterisation modelled after Hollywood star Gregory Peck was the sense of naturalism that Kumar brought to his characters, something that was unthinkable at that time.

While young actors migrate to Mumbai to become stars, Kumar became an actor perchance. Looking for a job, he happened to accompany Dr Masani, a psychologist who had come to Wilson college where had studied for a year, to Bombay Talkies where he was spotted by doyenne Devika Rani who headed the studio at the time. She offered him a job for `1,250 per month and in 1942, that was certainly a princely sum for the 20-something. She was also instrumental in changing his name from Yusuf Khan to Dilip Kumar, his screen avatar. It was at Bombay Talkies that he befriended the likes of actors Ashok Kumar, David, producer Sashadhar Mukherjee, directors Amiya Chakraborthy, Gyan Mukherjee and more.

It was in Amiya Chakraborthy’s Jwar Bhata (1944) that Kumar made his debut at 22. Though the film didn’t do too well at the box office, Kumar upped his game as he realised that the job was not easy. He watched Hollywood actors but was careful to create his own onscreen persona. It paid off as three years later, the 1947 drama, Jugnu opposite Noor Jehan was his first major hit. It was the highest-grossing Indian film of the year, thus establishing Kumar’s position. But there was more in store. In 1948, Kumar had five releases including a family drama Ghar Ki Izzat, a war film, Shaheed, a romantic tragedy Mela, a romance Anokha Pyar and Nadiya Ke Paar which further consolidated his position. In 1949, he featured alongside Raj Kapoor in Mehboob Khan’s Andaz opposite Nargis. This love triangle at the time of its release was the highest-grossing Indian film ever. Shabnam, another film released in the same year cast him opposite Kamini Kaushal, his co-star from Nadiya Ke Paar and Shaheed, the first of the many women that he was rumoured to be in a relationship with.

Of course, it was his pairing with the beauteous Madhubala — both on and off-screen — that caught the imagination of the nation. While the relationship did not last — and he went on to marry the much younger Saira Banu — the intensity scorched the screen in several blockbusters. The famous scene from Mughal-E-Azam, where Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahab’s vocals serenaded the duo in Prem Jogan Ban Jaye, is still considered the most sensuous one in Indian cinema, more than 60 years after the film’s release.

Incidentally, his portrayal of Prince Salim is the only one where Kumar — a Muslim — plays someone from his religion. Whether it was perchance or choice is a matter of debate. But what cannot be doubted are his secular beliefs and respect for all religions, castes, communities and creeds. He could quote the Quran with as much alacrity as the Bhagvad Gita while drawing parallels with the wisdom of the words of Bible. When he ‘sang’ a bhajan — Sukh Ke Sabh Saathi, Dukh Mein Na Koi, Mere Ram — in Gopi (1970), none could doubt his devotion to the God who is now perceived very differently from the time Kumar was a part of the film.

In that sense, he did represent the India that we set out to make which was equitable, just and secular. Meghnad Desai’s book Nehru’s Hero Dilip Kumar in the Life of India did chart out his journey as a parallel of a nation which was hopeful, aspirational and idealistic as personified by his films. Not surprisingly, Jawaharlal Nehru, the then Prime Minister, dropped on to the sets of Paigham (1959) to meet the actor. Later, in life, Kumar also hobnobbed with the likes of Bal Thackeray with whom he fell out as the politician demanded that the actor return the Nishan-e-Imtiaz, Pakistan’s highest civilian award in 1998. He also shared a warm relationship with former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and spoke to Nawaz Sharif when the former felt aggrieved over the Kargil incursion.

While the 1970s saw a slump in his career, beginning with Dastaan (1972) failing at the box office, in 1981, he returned with ensemble films. His comeback Kranti was the biggest hit of the year. He went on to star in director Subhash Ghai’s Vidhaata (1982) alongside Sanjay Dutt, Sanjeev Kumar, Om Puri and Shammi Kapoor. Later that year, saw the much-awaited Ramesh Sippy’s Shakti, where he was pitted against Amitabh Bachchan who played his son. A hit at the box office, the film won him critical acclaim and his eighth and final Filmfare Award for Best Actor. His last big-screen outing was in Qila in 1998

Kumar holds the Guinness World Record for winning the maximum number of awards by an Indian actor. He received his first Filmfare Award for Best Actor for Daag (1952) and followed it up with seven more. He also got a Lifetime Achievement Award from Filmfare as well as a Special Recognition FilmFare Award at its 50th award ceremony. He was nominated a record 19 times for the best actor. Kumar was appointed Sheriff of Mumbai (an honorary position) in 1980 and the Government of India honoured him with the Padma Bhushan in 1991, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1994 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2015. The Government of Andhra Pradesh honoured Kumar with NTR National Award in 1997.

In personal life, while he had simple tastes, there was perfection in those too. Catching a sunset, enjoying freshly baked bread with butter were some of the things he loved. As detailed in the foreword by Saira Banu in his autobiography, “He loves his simple white cotton attire, but the suave and sophisticated Dilip Kumar loves his beautiful collection of shoes, suits and ties too. I have learnt from him the finest way of maintaining these items. Down the years, I have loved to master the art of going through the various steps to achieve a good polish for the exquisite Dilip Kumar footwear, which are then lodged in shoe trees and wrapped in covers to keep off any moisture. His clothes are lined up and kept colour-wise: ‘White is white and off-white is off-white’ he has driven into our heads.”

Kumar believed in using his stardom to support good causes and raise funds for relief work. He led the first troupe that visited the Himalayan border areas to boost the morale of the Border Security Force personnel stationed thereafter India’s defeat in the 1962 Indo-China War among other initiatives.

While the man might have passed on to meet the greatest director of all, the actor continues to live in the hearts and minds of cine-goers.