Revisiting the Chipko Movement

Monday, 23 August 2021 | Lokesh Ohri | in Guest Column

HILLBILLY

Lokesh Ohri

Lokesh Ohri

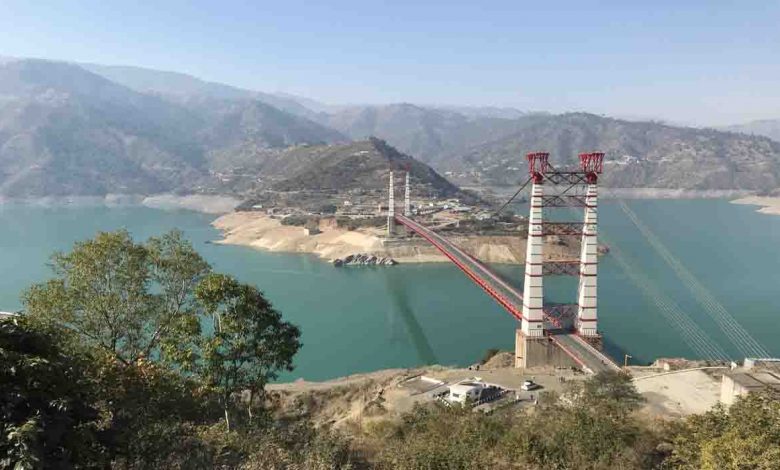

Chipko is a movement that caught the world’s imagination like no other effort to save the environment has been able to. Chipko and the anti-Tehri dam movements were perhaps the most significant milestones in the history of the state. They mobilised the people of the hills to fight for the forests and built a significant mandate for protecting the Himalayan rivers and hillsides. What is surprising is that post the period of political empowerment, with the coming of statehood, the state of Uttarakhand has spiralled uncontrollably into the dark vortex of environmental degradation and destruction.Today, not a whimper of protest is heard when hillsides are destroyed for roads leading to nowhere, and political parties can brush aside peoples’ protests against the taking over of elephant corridors for airport expansions.

In order to understand the spontaneous success of movements like Chipko and the subsequent failure of environmentalism in this state, one cannot find a better person to read than Shekhar Pathak, a chronicler of Uttarakhand, its history and culture. His recent book, Chipko Movement: A People’s History, gives a blow-by-blow account of the movement and encourages us to ask the crucial question of why environmental protest of today lacks teeth.

When, in 1974, the womenfolk and children of Reni village, under the leadership of the gutsy Gaura Devi were chasing away contract labour and their crony forest officials bent upon felling trees for commercial purposes, scripting perhaps the most significant chapter in the history of the Chipko Movement, a young scholar named Shekhar Pathak was undertaking with few others, a foot march from the easternmost fringe of Uttarakhand to its westernmost point. This, without a penny in the pocket, the group’s survival during the arduous trek entirely dependent on offerings from village folk. Having undertaken this difficult journey, popularly referred to as the Askot-Arakot Abhiyan four more times at an interval of a decade each, and his other numerous travels across the Himalayas, have given him an unrivalled understanding of the mountains and the people that inhabit them. No wonder then, Pathak catches every fine point of the people’s struggle for their environment and contextualises its events like no other author could have.

What emerged from the book is that the Chipko Movement became successful due to the efforts of Chipko’s foot soldiers – the peasants, students, women and children – who exhibited exemplary leadership in extremely adverse circumstances to protect their forests, relying completely on indigenous wisdom. These simple people were, not even aware of the emerging global discourse on ecology. That the awareness was slowly dawning is evident from the exasperated message from Agyeya, published in Nainital Samachar, a daily from the hills, for several issues on its front page, during the zenith of the movement. “Thousands of trees are felled to print one day’s newspaper. Therefore, writers should assess what they write in this light, and judge for themselves whether their articles are worth the felling of thousands of trees.”

Despite the movement being invoked by many, there has been no detailed history of Chipko until now. By giving us a ringside view as it were, of the movement, as it transformed from an effort to seize forest resources from the exploiters from the plains into a widespread agitation for a separate state and identity, the author has given us a deep understanding of how people at the grassroots themselves took responsibility for protecting and harnessing their resources for their future generations.

Described as a “definitive history” by noted historian Ramchandra Guha, who has also written the introduction to the book, the book brings to light several activists whose names had, even during the time of Chipko, been relegated to sub-texts only to appear in the pages of the vernacular media or minutes of the protest meetings. While acknowledging their role in protecting valuable community resource, which later came to be recognised as natural wealth critical to humanity, he has also reflected upon their often-impoverished circumstances and their familial struggles. Despite the odds, these mountain communities took on the might of the contractor backed forest officialdom that stubbornly refused to emerge from the colonial hangover of commercial exploitation of forests. Reading about these people’s struggles one gains an even more intimate understanding of the social context which persuaded these brave women and men to offer their bodies instead of trees, to the woodcutter’s axe.

While for the valiant women of Uttarakhand, the movement was an effort to regain the commons and stand up to the might of ruling classes – the dreaded nexus of the political, bureaucratic and contractor class – for many others, especially menfolk, it opened avenues for entry into identity politics. For the celebrated leaders of the movement, Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna, it was a crucible to test the ideas of Gandhi and Vinobha, to prepare a roadmap for social uplift in the isolated Himalayan hamlets.

Deciphering the myriad meanings entailed in a social movement defined by the one unique human response, “our bodies before our trees”, is no mean task. Pathak’s history achieves this with simplicity and in certain parts so involves the reader in the narrative that one becomes an active participant. He brings out clearly that for the mountain communities, ecology and economy can never be mutually exclusive of each other, with Chipko truly reflecting that social reality.

And to this insight is perhaps linked the conundrum of Uttarakhand’s current social and political malaise. For a region that rode on the back of ecological and feminist movements towards achieving separate statehood, today, has failed to produce a single political leader who could present to the people a new vision for a more secure future – environmentally as well as economically. The state has suffered so many chief ministers that it is difficult to keep track of the changes, and this has been a result of a poor understanding of community life on the part of our political class. Perhaps it is time for our younger politicians to read and understand the history of environmentalism in the state, and come up with solutions that offer ecological security rather than take us all on the path of ecocide.

(The writer is an anthropologist, author, traveler & activist who also runs a public walking group called Been There, Doon That? Views expressed are personal)