Birthing in the mountains

Monday, 04 October 2021 | Anjali and Sapna Negi

Anjali and Sapna Negi shed light on the plight of mothers-to-be residing in the hilly regions of Uttarakhand

Last year in February, 25-year-old Sunita, a resident of Pankholi village in Chamoli district of the hilly Indian state of Uttarakhand, died soon after delivering her child at home in a critical condition. Post-delivery, her health started deteriorating. Due to lack of telecommunication facilities, medical consultations or calling an ambulance were not an option. Helpless, the villagers decided to carry Sunita to the hospital on a chair along with her newborn and started walking towards the main road which was 3 kilometres from the village. Sunita and her child died even before reaching the main road.

Usha, a 28-year-old resident of Radagaad village in Kirtinagar Vikas Khand of Uttarakhand’s Tehri Garhwal district, ensured a similar fate. “After the delivery, my wife had developed serious complications and was being taken to Srinagar in Pauri Garhwal district. Unfortunately, she couldn’t even make it to the hospital and died on the way,” informed Anil Singh, Usha’s husband.

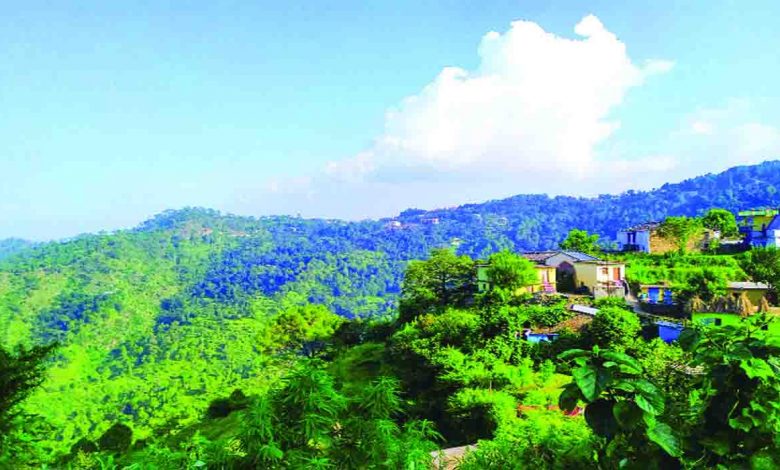

In hilly regions like Uttarakhand, villages are scattered, tucked away in mountains. These difficult to reach areas lack motorable roads, have poor telecommunication and health infrastructure. Locals have to struggle with availing basic health facilities. In situations like pregnancy, they are left to their own devices. Even if structures like Primary Health Centres (PHC) exist, there is an urgent need for physicians and basic facilities. Either the mother has to travel on twisted, unmotorable roads to give birth at a hospital or resort to home delivery, both being extremely unsafe. On several occasions, women have given birth on roadsides or in forests.

In October 2017, Binita, a resident of Ishali Thunara village in Uttarkashi district, was brought to a PHC at Tiuni in Dehradun’s Chakrata block for delivery. Due to the absence of the doctor, the staff did not even allow them to enter the building. To make matters worse, no ambulance could be arranged to take them to another hospital. Family members decided to take Binita to the nearby city of Rohru in Himachal Pradesh and started walking from the PHC towards the Tiuni market. Binita’s pain escalated on reaching a suspension bridge approximately 300 metres away from the centre. With the help of local women, a closed area was set up using bed sheets. These women helped Binita deliver her child. Despite the testing situations, both the child and the mother were healthy.

According to the Healthy States Progressive India Report, 2019, published by Niti Ayog, the state of Uttarakhand was relegated to the 17th rank out of 21 states, from the 15th rank in the previous year’s report. The state has performed badly in most aspects, including infant mortality rate (IMR) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR). However, a report by the National Health and Family Welfare-4, Uttarakhand, states that 69 per cent of births take place in a health facility, mostly in a government facility. But the question remains — why do the remaining 31 per cent still have no proper access to institutional delivery?

The responsibility of pregnant women’s health rests majorly with ASHA workers and ANMs in rural areas. Anju Devi, an ASHA worker from the Pipleth village of Henwal Ghati, pointed out that health check-ups and vaccinations of pregnant mothers are done regularly. While another ASHA worker, Usha Negi from Than gram panchayat in Narendra Nagar Block in Tehri Garhwal district, said, “Health facilities are available but due to the distance, pregnant mothers have to travel more than 6-7 kms from their villages to get medical facilities.”

Dr Sandeep Gurjar, the medical officer-in-charge of the Community Health Centre in the Khari region in Tehri Garhwal district’s Narendra Nagar Block, informed about the facilities available in the medical centre. “Despite being a new hospital in a remote area, we do provide delivery facilities. Resources are being mobilised right now. Serious deliveries that require an operation have to be referred to a specialised centre through the 108 ambulance service,” shared Dr Sandeep. While narrating his experience, he mentioned that their team tries to facilitate delivery services for the village women so that they are not forced to go to nearby cities to avail these services.

According to Dr Rajeev Negi, the Maternal Health in-charge of Tehri Garhwal, a death audit is also conducted when a woman dies during pregnancy and childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy at the village or household level. Arrangements have been made by the government to give an incentive of `1,000 to those who inform about the death of a pregnant woman. On receiving the information at the district level, the Chief Medical Officer’s office appoints a team of senior doctors to investigate the cause of the death of the pregnant woman at the village level through a death audit.

Reflecting on the reasons for the death of pregnant women, Dr Negi said, “In most of the cases, neglect of medical advice, negligence in taking medicines due to heavy workload and anaemia have been observed.”

All the health workers also stressed on the availability of 108 free ambulance services in the state which facilitate institutional delivery. But how will the villagers make use of this service without proper telecommunication and road infrastructure. Also, why are women in these remote areas deprived of proper care and facilities during their pregnancy despite the presence of several health provisions?

In the current times of Covid-19, women in these areas are facing double challenges. While most of the health centres have been converted into Covid-19 facilities, we can only imagine the pain of the pregnant women coming from these far-flung, remote, and hilly areas!

—Charkha Features