Redrawing the map: Understanding Uttarakhand’s delimitation process

GUEST COLUMN

The large gathering in Chennai recently reignited the debate on delimitation. The gathering included leaders from several States, including four chief ministers, at the inaugural meeting of the Joint Action Committee (JAC) on Fair Delimitation. They delivered a clear message that a delimitation exercise based solely on current population figures is unacceptable. The delimitation of constituencies for the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies is scheduled based on the first Census after 2026. The politicians of southern States have alleged that the region is being ignored unlike the northern States, arguing that since the majority of the country’s population resides in northern India, most resources are allocated to those States. Some southern States have expressed their decades-old concern about the potential loss they might face in the upcoming delimitation process based on population. However, this analysis is not about the north versus south debate but rather a similar issue concerning another region.

On November 9, 2000, Uttarakhand became the 27th State of India and the 11th Himalayan State, carved out of Uttar Pradesh. The demand for a separate Uttarakhand had been raised even before India’s independence. This demand intensified in the last decade of the 20th century, stemming from the growing resentment over stark inequalities between the plains and the mountainous regions of Uttar Pradesh. As time passed, these inequalities deepened. The solution was found in the form of a separate hill State, where the focus would be on hill-centric planning and, more importantly, a hill-centric ideology to bridge this gap. Thus, the creation of Uttarakhand aimed to center political power, administrative systems, financial resources and overall governance on the needs of the mountainous regions.

The first interim Legislative Assembly of the State was formed with 30 members, who were previously elected from the same region under Uttar Pradesh. Among them, 19 members represented the hills and 11 members represented the plains. This interim government functioned until 2002 when the first State Assembly elections were scheduled, necessitating a delimitation process.

Before understanding the division of seats in the 2002 delimitation, it is important to comprehend the delimitation process itself. Delimitation is a constitutional, political and administrative process under which the boundaries of Lok Sabha and State Assembly constituencies are determined based on the population of each region. This process ensures that each elected representative represents a relatively equal number of people. Delimitation is conducted by a Delimitation Commission in accordance with Article 82 and Article 170 of the Indian Constitution, working in collaboration with the Election Commission. Since India’s independence, Delimitation Commissions have been constituted in 1952, 1962, 1972 and 2002, with the next scheduled delimitation set for 2026. The commission is established based on the most recent census to account for population changes—benefiting regions with growing populations while posing disadvantage to those experiencing population decline. This aspect of the commission’s functioning often brings it under scrutiny.

Uttarakhand is among the Himalayan States where the search for better education, healthcare, employment and infrastructure has triggered mass migration from the hills to the plains. Historically, the hills have been marginalised regarding basic facilities, leading people to migrate toward the more developed plains. This trend has accelerated since the formation of the State. Consequently, the hills are depopulating, while the plains are witnessing a surge in population. As previously mentioned, the Delimitation Commission bases its work on population data, meaning migration from the hills to the plains directly disadvantages the hilly areas during the delimitation process.

Considering the specific geographical and social conditions, special provisions have been made to determine Assembly and Lok Sabha constituencies in some States under Article 371 of the Constitution. According to Article 81(2)(a), the population of all Lok Sabha seats in the country should ideally be the same. However, in Uttarakhand, Ladakh and other Himalayan States, the number of people per Lok Sabha seat is much lower than in other States. Despite unequivocal constitutional provisions for Lok Sabha constituencies, some exceptions have been made based on special situations, indicating that the same kind of consideration might also be extended to Assembly constituencies.

Sections 9 and 10 of the Delimitation Act, 2002, mention that delimitation should take into account specific geographical features, disparities in administrative units, availability of communication facilities and public amenities. However, in Uttarakhand, these geographical conditions and other criteria have been overlooked, and only population has been used as the sole standard for delimitation. Although Articles 82 and 170 of the Constitution consider population as the basis for delimitation, the phrase “so far as practicable” is used, implying that special exemptions are possible for States facing challenging conditions.

At the time of the State’s formation, keeping in mind the concept of a mountainous State, 42 Assembly seats were allocated to the mountainous region and 28 to the plains. However, later delimitation based only on population ignored this early vision, which is entirely against public aspirations and erodes the State’s very foundation. In contrast to other Himalayan States, the special rural situation, rugged geographical terrain and poor communication and public facilities in Uttarakhand were not considered at the time of delimitation, resulting in adverse effects on rural development. Since the 2000 delimitation, the distribution of Assembly constituencies has deviated significantly from the original vision of a balanced mountain State.

The Delimitation Commission for the 2002 elections was chaired by Justice Kuldeep Singh, which established 70 Assembly constituencies in Uttarakhand—40 in the mountains and 30 in the plains. Geographically, 9 out of 13 districts in the State are entirely mountainous, Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar are completely in the plains, while Dehradun and Nainital are partly plain and partly hilly. Following this first delimitation, political power remained largely centered in the hills. However, as mentioned earlier, migration from the hills to the plains increased after the state’s formation, leading to further losses for the hills during the national-level delimitation after 2002.

The present political setup of Uttarakhand shows an increasing disparity between the hilly and plain areas. Of the 70 Assembly seats in Uttarakhand, 36 are in the plain regions. This implies that if any political party wins all these 36 seats in the plain region, it can form the government without any support from the hilly areas. Such a situation sidelines the concerns of people living in the mountains and undermines the purpose of creating Uttarakhand as a separate state to address the specific needs of its hilly areas.

In Uttarakhand, significant disparities exist in the distribution of MLA seats between mountain and plain districts. Chamoli and Uttarkashi—two of the largest districts by area with a combined geographical expanse of over 16,000 square kilometres—are allocated only six MLA seats. In contrast, the four plain districts—Nainital, Udham Singh Nagar, Haridwar, and Dehradun—which together cover 11,406 square kilometres, consist of 36 MLA seats. This imbalance highlights the challenges in ensuring equitable political representation across regions with vastly differing geographical and demographic profiles.

In the upcoming delimitation, adopting a more holistic approach that considers not just population but also geographical diversity, the availability of natural resources, and the developmental challenges in the hilly areas is essential. Providing just representation through a balanced allotment of seats will not only strengthen democratic rule but also uphold the very purpose of Uttarakhand as a State devoted to the well-being of its mountain communities.

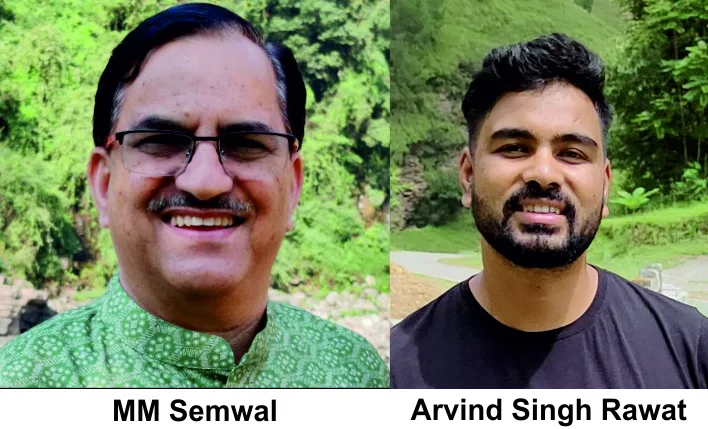

(Semwal is head of political science department at HNB Garhwal Central University, Rawat is senior research fellow in the department; views expressed are personal)