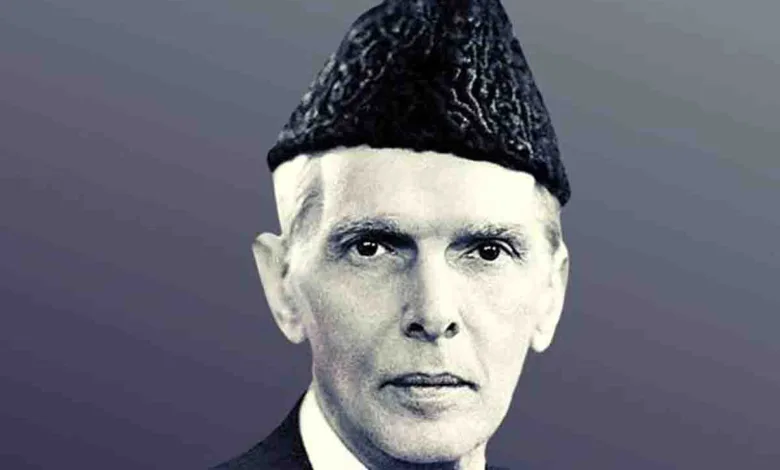

VIEWPOINT : Conundrum of real-unreal M A Jinnah

Romit Bagchi

Romit Bagchi

Over 75 years have passed since the ancient land of Bharat was divided on communal lines and two States-India and Pakistan- came into existence and yet the venomous animosities involving them continue undiminished. While I was looking back on the blood and tear-soaked history preceding the Partition, my focus stayed stuck on Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founding father of Pakistan who, while he was still in India, said with arrogance tinged sarcasm that he had founded Pakistan with the help of his typewriter and stenographer.

Many years ago when I was still in college I read a book on Jinnah in Bengali written by a researcher Shailesh Kumar Banerjee, who was a staunch follower of Mahatma Gandhi. The book was an attempt at reassessment of Jinnah and his role in that tense, turbulent time when things were in a dangerous state of flux, when an embattled nation kept groping uncertainly to lay hold on its destiny, struggling hard to break free from the yoke of the colonial rule. My earlier idea of Jinnah as a cold, calculating and snooty politician infamous for vituperative speeches, preaching hatred for everything Hindu and hurling venom-laden invectives on the revered leaders of the nation started to change. I read in Banerjee’s book that when the time came for Jinnah to leave Delhi for Karachi as the Governor General (designate) of Pakistan on August 7 1947 he gave a message to Hindustan the concluding part of which seems filled with a poignant sense of loss: “I bid farewell to the citizens of Delhi amongst whom I have many friends of all communities and I earnestly appeal to everyone to live in this great and historic city with peace. The past must be buried and let us start afresh as two independent sovereign States of Hindustan and Pakistan. I wish Hindustan prosperity and peace.”

On August 11 1947, he addressed the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Let me quote an excerpt from it. “On both sides, in Hindustan and Pakistan, there are sections of people who may not agree with it (Partition), who may not like it, but in my judgment there was no other solution…Any idea of a united India could never have worked and in my judgment it would have led us to terrific disaster. Maybe that view is correct; maybe it is not; that remains to be seen…Now what shall we do? Now if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous, we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people…If you will work in cooperation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that everyone of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make. I cannot emphasise that too much. We should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community…will vanish.”

In the concluding part of this address he said significantly: “Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.”

Was this the real Jinnah whom the poetess Sarojini Naidu famously called ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’ when he, a westernised liberal, was an active member of the Indian National Congress resolutely wedded to the pluralistic nature of Indian society? Many historians and biographers of this enigmatic personality have opined that the real Jinnah remains unrevealed in history.

But one thing is certain: his persistent and passionate advocacy for the two-nation theory, partition of India and creation of Pakistan as a homeland for the Indian Muslims could hardly go with his highfalutin call for enduring peace with India and his emphatic stress on the minorities in newly formed Pakistan being seen as equal to the majority with respect to rights and privileges.

Why? The late BJP leader Jaswant Singh has given the right answer in his much-debated book that landed in fierce controversy immediately after its publication-Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence. “Mohammed Ali Jinnah was, to my mind, fundamentally in error proposing Muslims ‘as a separate nation’ which is why he was so profoundly wrong when he simultaneously spoke of ‘lasting peace, amity and accord with India’ after the emergence of Pakistan; that simply could not be. Perhaps, late General Zia-ul-Haq was nearer reality, when, asked as to why Pakistan cultivated and maintained this policy of induced hostility towards India, he replied (some say apocryphally, but tellingly) that ‘Turkey and Egypt, if they stop being aggressively Muslim, they will remain exactly what they are. But if Pakistan does not become and remain aggressively Islamic it will become India again. Amity with India will mean getting swamped by this all-enveloping embrace of India.’ This worry has been haunting the psyche of all the leaders of Pakistan since 1947.”

So, may we say that it is a compulsion for Pakistan to aggressively flaunt its separateness as an Islamic nation, distinct from India? Jaswant Singh writes: “In reality this has impeded Pakistan’s coming into its own, evolving into a modern, functioning State. Sadly, a reasoning and credible national identity eludes it still. From becoming an Islamic State, Pakistan, ultimately, again perhaps inevitably, had to become a ‘jihadi State’ and when set on this path, it also then became, again perhaps inevitably, the epi -centre of global terrorism.”

In retrospect, it indeed seems that the two-nation theory hangs like a dead albatross around Pakistan’s neck: an inescapable burden, hindering its progress to become a modern State.

Coming back to Jinnah, it is still murky as to whether he was happy or frustrated with the creation of Pakistan. He did not live long enough after Pakistan was carved out of Bharat to explain his view. So, over 75 years after his death, his persona remains as tangled and elusive as ever.